|

Violin Italian method of making |

|

The technique of embedding the purfling after gluing the plates onto the ribs is a tradition that arose from viola da gamba construction. Their plate edges –without purfling channel or overhang– made this technique possible. It lasted through the construction of string quartet instruments until the process became industrialized. Nevertheless, some schools still teach this method along with the modern one.

Each workshop –from centuries past or modern– has its own practices; each violin maker has his individual touch: nothing has changed, except technology. This is why, then as now, there exist different manners for using the Italian technique for edgework and the purfling channel on the free materials and glued onto the ribs, which makes this technique much more complex than it seems.

· Trim the edges before or after assembly on the ribs;

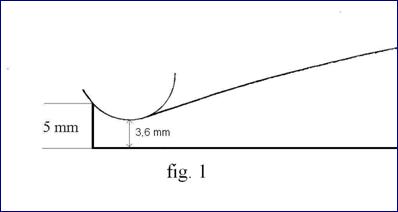

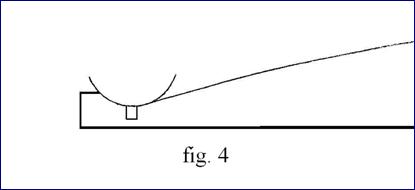

· 5 mm edge thickness, sharp ridged edge and channel (fig. 1) or flat 2 mm wide ledge (fig. 4);

· Finished, pre-finished, or unfinished purfling channel, before assembly.

Depending on the technique used, the quantity of wood removed to finish the edges and purfling channel on the mounted materials will be different, yielding aleatory frequencies for both the free materials and the coupling frequencies as well as modes B1- and B1+.

To use the Italian technique, proceed in the following manner:

1) Outline the plates’ edges, following the rib garland that has been glued into the mold.

2) Cut out the plates.

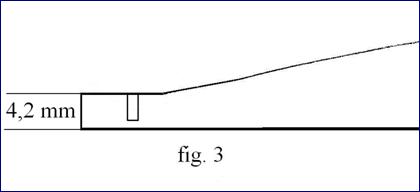

3) Rough out the extrados leaving 5 mm thickness on the edges, or create a platform as in fig. 3.

4) Then trim the edges of the free materials.

5) Hollow out the purfling channel according to figure 1, or using the modern technique (fig. 4).

6) Use the modern method described in this book (without gluing in the purfling) to tune the mode 5 of the starting volume extrados of the back and top plates, completely finished, using the tables of the book.

In order to obtain a mode 5 frequency for the free materials’ intrados, identical to that listed

7) Tune the mode 5 frequency of the intrados of the back and top plates, using the tables in this book “The Sound of Stradivari”.

8) After tuning the mode 5 of the intrados of both plates (before cutting the f-holes and gluing

9) Cut the f-holes, glue in the bass bar, and tune the mode 5 of the top plate with its bass bar, using the table of the book “The Sound of Stradivari”.

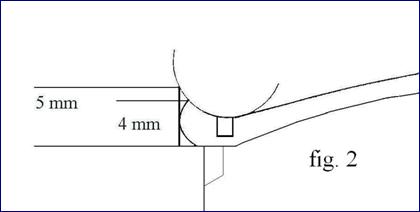

On plates glued to the ribs: · Open the mortise and glue the purfling. · Proceed with finishing the purfling channel as well as the edges (fig. 2). · Finish the body overall. · Thickness at the deepest point of the finished purfling channel: 3.5 mm.

Greater thicknesses can be left in the corners and the “C”, as well as on the back plate button (technique used by the Italian makers and likewise valid for modern violin making).

The B1- and B1+ body mode frequencies (with or without the neck) will be approximately the same as they would be using the modern method (with the same moisture content of the materials).

As with the modern method, when the free materials are perfectly tuned, it is not necessary to know their coupling frequencies (via generator or software). Nevertheless, violin makers conducting research should proceed as follows, using software:

To read the tap-tone of each plate glued separately onto the ribs, hold the back or top plate at

N.B. The Italian technique (fig 1 and 2) can be used for edgework and the purfling channel

Modern technique

Free materials: · Outline the plates’ edges, following the rib garland (with an inside mold) or use a template · Make a platform on the edges 4 to 4.2 mm thick, including the back plate button (fig. 3); · Trim the edges , · Open the mortise and glue the purfling; · Excavate the purfling channel, leaving a flat 2 mm wide horizontal edge (fig. 4); · Thickness at the deepest point of the finished purfling channel: 3.5 mm; · Tune the starting volume with the extrados completely finished. · Hollow out the intrados, tuning mode 5. · Cut the f-holes, glue in the bass bar, and tune the mode 5 of the top plate with its bass bar,

Comments

When building their instruments, the Italian violin makers used a simple and reproducible technique, consisting in shaping the starting volume of the extrados (exterior) of the top and back plates by seeking their respective notes, before carving out the intrados (interior).

Plate tuning was accomplished by tapping, then comparing the note heard with any instrument producing sound. Embedding the purfling, scraping, and finishing the edges were executed on the top and back plates glued separately onto the ribs.

Thickness graduation in the purfling channel, in the center, or in the intermediary regions enabled

Although their technology may appear somewhat rudimentary to us today; the Italians masters had real intellectual capacities, as well as perfect mastery of their tools and their profession, as proved by their instruments exhibited in museums.

Wood is a living material for as long as it can absorb and release water vapor, even after the instrument has been varnished.

This tried and tested technique was known even before Stradivari’s “golden age.” However, lengthy training must have been necessary before achieving accurate tuning of the materials by this empirical method, due to the recurrent hygroscopic instability of the wood, particularly in an unheated workshop.

Many researchers and makers believe the secret of Italian violins resides in a mass or surface treatment of the wood that has altered the materials’ acoustical characteristics. The superiority of Stradivari and Guarneri violins was recognized as soon as they were manufactured. If a treatment of the wood was one of the main reasons for their superiority, we can deduct that it was effective immediately.

All techniques that enable improvement in the materials’ performances are valid. Nevertheless, processes such as kiln drying, salt-solution stewing, water seasoning, chemical (ammonia) or fungal treatments, or constraints exerted on the materials (increasing the longitudinal Young’s modulus) cannot in themselves significantly increase the frequencies of unworked materials, if, from the outset, the wood has been cut in the wrong direction or has low performances.

In his treatise, Félix Savart pointed out the problems in violin plate tuning entailed by moisture in the wood. Legend has it that the Italian violin makers fashioned their instruments during the winter and varnished them in the summer. All legends are based on an element of truth.

The difference between antique and modern violins must be sought in the development of a forgotten methodology.

Even during his lifetime, Stradivari was the world’s most famous violin maker. The greatest center for violin making during the 17th and 18th centuries was Cremona, where kings and their courts ordered their instruments, and each workshop had its own techniques, handed down verbally from father to son or from master to student.

The method explained in this book enables the reader to understand and learn the tuning technique used by Stradivari, Guarneri, and other Italian makers, but with recourse to modern devices so as to avoid those failures due either to a bad choice of materials, or to a rapid change in moisture content of the wood during the tuning process.

The top and back plates will be entirely completed by reproducibly tuning them within a restricted frequency spectrum specific to the solo violin with minimal weight, thus enhancing the instrument’s performances.

Clarity of the timbre is first and foremost conferred by the height of the top plate’s coupling frequency. The sensation of a clear timbre is intensified by the height of the A0 and A1 mode frequencies as well as that of the mode B1+ frequency. If the combination of these three frequencies is too high the violin will be at the point of saturation.

The difficulty encountered in violin acoustics has always been to understand and acknowledge the difference between the old masters' technology and that available to us today. What do we know about Italian violins? That they have an extraordinary sound! We are seeking that which has already been found, while remaining unaware of the method: that is the veritable secret!

Over the course of two centuries, many explanations and hypotheses have been proposed, and in particular, the recipe for a varnish with wondrous properties, forever lost. In fact, it is simply a matter of understanding the laws of acoustics applicable to the violin, as well as the laws of physics concerning the structure of the constituent materials.

The art of violin making is so complex that it melds with science. Certain processes obtained through structured knowledge, close observation and objective experimentation (empiricism) can be considered as belonging to the realm of science. Once they have been mastered, they remain simple workshop techniques perfected by highly trained craftsmen. This simplicity enabled the Italians to construct their finest violins without the help of our modern technological methods (albeit with a variable rate of success, due to variations in the moisture content of their materials).

After a change in the practice or the disappearance of a craft, these techniques become secrets. An historic process has eluded us; our modern means prevent us from distinguishing between myth and reality, between science and art. With the passing of time, they came to be considered as magical; intense questioning and reasoning yielded to mystification.

Is the secret of Stradivari violins a myth or a reality? In fact, it is simply a matter of understanding traditional techniques developed by highly skilled craftsmen based on the laws of acoustics specific to the solo violin, that were then abandoned in favor of rational methods ascribable to the cultural evolution of society.

After 1700, Stradivari improved his predecessors’ tuning technique to solo violin performances inspired by new forms of music. His research, by no means based on chance or ignorance, led him to determine the area of the mold (its flat surface) as well as the length of the body. In order to increase the violin’s carrying power without altering the cavity frequency, he reduced the area of the f-hole apertures and lowered the arching to reduce the volume of the resonance chamber. This likewise enabled him to reduce the weight of the materials yet maintain the same thicknesses.

The genius of Stradivari lies in having identified and resolved the tuning problems specific to the solo violin with such limited means.

There never was a secret to Stradivari’s violins. The tuning technique was familiar to all the Italian violin makers. Some craftsmen, more successful than others, may have maintained a policy of secrecy. Nonetheless, it is established that we owe the definitive perfection of the violin to Stradivari, whose closest competitor was Guarneri “del Gesù.”

In the second half of the 18th century, music became more widely available to the various social classes throughout Europe, and violin making likewise spread and flourished. The first violin factory was established in Mirecourt (France) around 1790 by Didier Nicolas. The manufacturing process was rationalized by the division of labor. Later, with the industrial revolution, bowed instruments were mass-produced in other European cities, as well.

In accordance with a well-known process of man's cultural evolution, a hiatus in the transmission of know-how occurred. The Italian masters' violinmaking techniques were lost and gave way to production for a much wider public. This often heralds a change in the craft, or the disappearance of a trade. Previously known techniques then become secrets. With time, "magic" intervenes and reason yields to mystification.

Copyright © 2010 - 2019 Patrick Kreit. Reproduction of any content of this site without my express written permission is prohibited

|